When San Jose’s City Council recently voted 11-1 to resume “sweeps” that would wipe out homeless encampments around the city, the news hit one group of young adults especially hard.

“It was kind of shocking,” said Danielle Graugnard, a law student at Santa Clara University School of Law, who heard the news the next afternoon during a Zoom class. “Sweeps aren’t good for anyone, and they are taking the people in the encampments back to square zero” by making it harder to facilitate COVID-19 vaccinations, services, or finding stable housing.

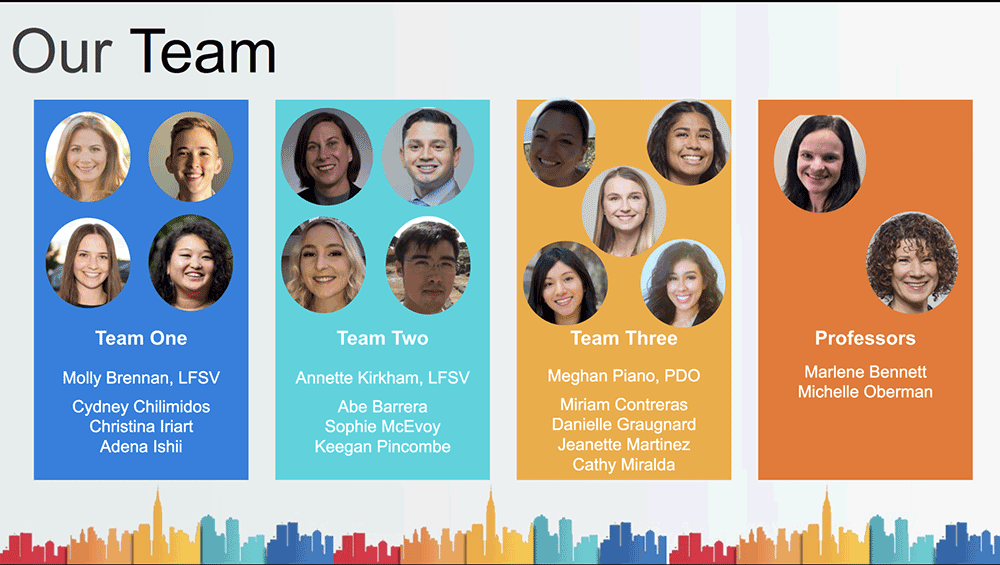

Graugnard and nine fellow students have a distinctive reason to care about the fate of those lacking homes in the Bay Area: they are part of an unusual law class, Criminalizing Homelessness, which tasks the students with charting the way Santa Clara County or other localities currently invest homelessness-related resources.

The students have spent the current semester investigating three areas — mental health and social services, temporary housing, and criminal law — calling attention to practices that are both wasteful and inhumane. Their work culminated in a Zoom presentation on April 21 before several dozen key stakeholders — city council council members, law enforcement leaders including Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, and leaders of numerous community-based organizations.

The course is co-taught by professors. Michelle Oberman and Marlene Bennett ’04, JD ’08, a veteran public interest lawyer, with pro-bono help from three SCU alumnae with years of expertise in working with unhoused clients: Meghan Piano ’04, JD ’07, a veteran public defender; Annette Kirkham JD ’01, senior attorney in the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley’s Housing Program; and Molly Brennan JD ’09, senior attorney with the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley’s Health Program.

The students — most of whom are in their second year like Graugnard — are assigned to research the ways in which Santa Clara County is responding to the needs of residents who are experiencing homelessness. Rather than simply advocating for the widely accepted — yet elusive — goal of finding permanent housing, the class seeks to present data-driven conclusions and alternatives from other regions with best-practices solutions.

Along the way the students have made many eye-opening discoveries:

- The shocking lack of data held by local governments, which makes proposing solutions with a provably good chance of success nearly impossible. “I had to submit a public records request for the number of shelter beds,” said Christina Iriart, a second year law student. What she got back in response was a simple excel sheet with bed counts—and no indication of where they were currently allocated. “It’s hard to find solutions to a problem when there’s not a lot of data tracking,” she said.

- The fact that even with data-backed solutions in hand, sometimes local governments just aren’t ready to tackle the quest for solutions. “In Gilroy, there’s a 58 percent chance people will move on to better housing if you provide them a safe place to park” their RVs or cars, said student Abe Barrera, who is in his fourth year studying for both his MBA and law degree. But, “if it’s not the right time (for the council to address the issue) it’s still going to be very difficult to get something done” on safe parking laws, he said.

- The conflicts of interest that arise when city council members own companies that benefit from regressive policies like towing homeless peoples’ cars, or own housing-construction companies.

- The close ties between heavy policing in a region and poor outcomes for homeless people.

- The lack of resources to implement successful ideas. Santa Clara County only has three “service navigators” serving 464 former inmates re-entering society (with thousands more who could use such services). That’s a woefully small number for a program proven to stabilize those who need help after incarceration, said Graugnard.

For many, this class has been the first time they’d ever thought about the legal treatment of those without homes, and some plan to continue working in this area.

“I knew I had a passion for social justice and helping people,” said Iriart. “But learning about these issues and how housing is such a huge issue in the county, Bay Area, and in general had a huge impact on me,” she added. She sought out and secured a position for this summer with Bay Area Legal Aid, in their housing unit.

Other students have had their own experiences with housing insecurity, or being part of marginalized communities, and aren’t quite as surprised by the lack of focused solutions.

“When the city is catering to people who are in million-dollar homes, it really just makes sense that homeless are the ones who are going to be forced out,” said second year law student Cydney Chilimidos, who, as a gay student with a disability, plans to fight as a lawyer and advocate for disability rights. “It’s really important that people who are living the experience in question are the ones who actually talk about it.”

The class was spurred by a previous class on COVID-19, in which students examined how the pandemic had affected public-health law issues such as conditions within Santa Clara County jail, and access to housing for people living with HIV/AIDS. One topic in that seminar that felt ripe for further exploration was homelessness, said Bennett. She and Oberman had conversations with various stakeholders in the county’s legal and homeless services systems to help structure the course most effectively.

“These conversations really drove home the many ways in which Santa Clara County’s current response to homelessness is punitive and costly — literally and figuratively,” said Oberman. “These students are mapping the way Santa Clara County currently invests resources in serving the very predictable needs of the unhoused, while also studying best practices around the country to suggest smarter alternatives.”

The students presented their findings April 21 in a one hour Zoom presentation to more than 35 key local leaders and advocates. By sharing the cycle that too often traps people experiencing homelessness, and by highlighting potential junctures where the county might readily create “off ramps” out of that cycle, the students are hopeful that their work illuminated effective and affordable alternatives to the county’s present approach, and encouraged greater collaboration among stakeholders.

They also hope their work will remind public officials that there are a wide array of people who care about reaching humane solutions, and not just sweeping the problem under the rug. “The general population doesn’t really know about this, because it’s been hidden from society by laws that push people further and further away from nicer areas,” said Barrera. “We don’t want to see this side of society, but it’s there.”

Added second year law student Adena Ishii: “I think the most important thing we can do is make sure they know that we’re watching them, we’re paying attention, and we want to see a change.”

“I have been so proud to see these students becoming leaders in advocating for social change,” said Oberman. “It is truly what sets Santa Clara Law apart—our dedication to using education to help those who are increasingly marginalized, especially as social divides become harsher amid the pandemic.”