Blog post by IHRC student Jessie Smith and Prof. Francisco Rivera

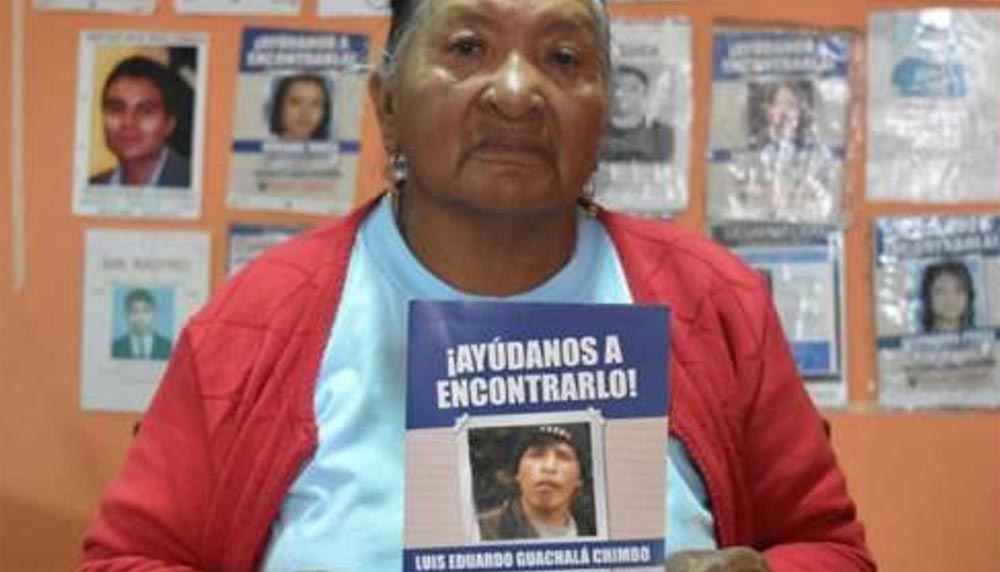

Zoila Chimbo, mother of Luis Eduardo Guachalá Chimbo, with a sign that says “Help us find him” (photo credit).

Santa Clara Law students Jessie Smith, Linnea Eccleston-Banwer, and Pree Sandhu, of the International Human Rights Clinic, submitted an amicus curiae brief before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Court), under the supervision of Prof. Francisco Rivera. This brief addressed the human rights violations associated with Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s disappearance while in the custody of a public psychiatric hospital in Ecuador.

On January 2004, Mr. Guachalá Chimbo disappeared while under the custody of Julio Endara Psychiatric Hospital in Ecuador. Over 16 years later, Ecuador has not determined the truth of what happened to Mr. Guachalá Chimbo; his whereabouts or his fate is unknown. Since Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s disappearance, his next of kin diligently searched for him, while the hospital and state authorities failed to effectively investigate his disappearance.

The brief addresses two main issues: 1) whether Mr. Guachalá Chimbo – a person with a mental disability – was required to give his consent to being institutionalized and to receive medical care, and 2) whether the State could be held internationally responsible for his disappearance form a mental health institution. In its judgment of March 26, 2021, the Court agreed on both issues.

The brief asked the Court to hold Ecuador responsible for violating Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s rights to juridical personality, freedom of expression, and health, recognized in Articles 3, 13, and 26 of the American Convention of the Human Rights, by not obtaining his informed consent at a mental health institution. Ecuador did not obtain Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s informed consent when it admitted him to the hospital, gave him treatment, and kept him admitted when his alleged medical emergency ended. Instead, Ecuador asked Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s mother to sign pro forma hospital admission documents and restricted Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s ability to decide for himself whether he wanted to be admitted and remain at the hospital. Ecuador’s failure to obtain his consent was based exclusively on the assumption that a person with a mental disability is unable to provide consent. Such assumption is based on a prohibited form of discrimination under international human rights law. Therefore, the brief urged the Court to adopt the criteria developed by the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to recognize that persons with disabilities are subjects of rights who must provide consent for themselves, except in very exceptional circumstances. In its judgment of March 26, 2021, the Court agreed and found that the use of the victim’s disability to justify the State´s failure to obtain his informed consent for hospitalization and medication, constituted discrimination.

Regarding the second issue, the brief requested that the Court declare Ecuador responsible for the disappearance of Mr. Guachalá Chimbo from a public psychiatric hospital while under the care and custody of the State. Forced disappearances are complex human rights violations that affect the rights to life, personal integrity, personal liberty, and access to justice, recognized in Articles 4, 5, 7, 8, and 25 of the American Convention on Human Rights, and in Articles II and III of the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance.

According to the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons and the Court’s jurisprudence, the following elements must be established to prove that a forced disappearance has occurred: 1) deprivation of liberty; 2) the direct intervention of State agents or their acquiescence, and 3) the refusal to acknowledge the detention or reveal the fate or whereabouts of the victim. The overarching theme is the denial of the truth about what happened to the disappeared person.

Although most cases of forced disappearance before the Court have taken place in a context of widespread and systematic human rights violations, usually in times of civil unrest and dictatorial regimes, in this case the facts took place in times of peace and democracy. The brief therefore asks the Court to expand the concept of forced disappearance to the context of patients who disappear in the custody of a public mental health institution. Despite the different context, the underlying characteristic of forced disappearance – the deprivation of information and concealment of the truth — remain the same. Mr. Guachalá Chimbo disappeared while under the care and custody of Ecuador. Even though almost 17 years have passed since his disappearance, the state authorities have not provided his mother with information about her son’s fate or whereabouts.

In its judgment of March 26, 2021, the Court held that the State was unable provide a satisfactory explanation as to the disappearance of Mr. Guachalá Chimbo and, at the very least, was negligent in preventing his disappearance, which violated his rights to life and personal integrity.

The clinic’s brief also asked the Court to consider the suffering of Mr. Guachalá Chimbo’s mother and declare Ecuador responsible for the violation of her right to freedom of personal integrity, recognized in Article 5 of the American Convention on Human Rights. The Court agreed.

A video of the hearing before the Inter-American Court (in Spanish) can be found here. More information about the case (in Spanish) can be found here. The Inter-American Commission’s decision on the merits can be found here. The Court’s judgment can be found here. The Clinic’s brief can be found here.

IHRC student, Jessie Smith.