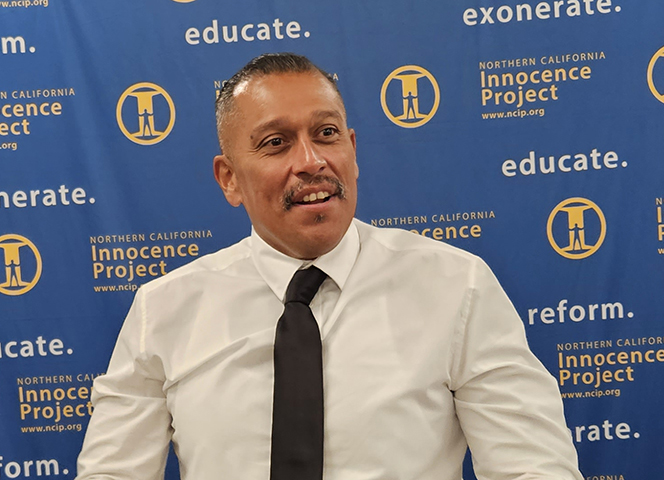

After spending 25 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit, Miguel Solorio was released from Mule Creek State Prison on Monday, Nov. 13. There in the parking lot to greet him were his lawyers and legal team from Santa Clara University School of Law’s Northern California Innocence Project, who had been fighting for this day for more than a year.

“This nightmare started when I was 19 years old,” said Solorio. “I’m now 44. This was going to be my 25th Christmas in prison. Being home this year will be the best present ever.”

A Fateful Utterance

Solorio was arrested in 1998 for a fatal drive-by shooting in Whittier, Calif., and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

Police had zeroed in on Solorio as the lone suspect after hearing that someone had uttered his nickname during the crime. Despite numerous clues that he was not guilty —eyewitnesses who failed to pick him out of an initial photo lineup, two alibi witnesses, and the suspect car not being registered to him and driven by the true perpetrator —police failed to follow up on other suspects. And in their zeal— as the District Attorney’s office would end up admitting 25 years later—police ended up tainting the eyewitness evidence that would eventually put Solorio away.

“This case is a tragic example of what happens when law enforcement officials develop tunnel vision in their pursuit of a suspect,” says NCIP Staff Attorney Sarah Pace. “Law enforcement officers put their own judgment about guilt or innocence above the facts.”

“This case is a tragic example of what happens when law enforcement officials develop tunnel vision in their pursuit of a suspect,” says NCIP Staff Attorney Sarah Pace. “Law enforcement officers put their own judgment about guilt or innocence above the facts.”

A New Consensus on Eyewitness ID Practices

The case against Solorio heavily relied on the use of photo arrays to obtain eyewitness identifications. But the process was troubled: Four witnesses failed to identify Solorio in the first photo array they were shown—with some even choosing a different suspect. Police then showed two witnesses further arrays in which Solorio was the only one featured in all, until finally, some witnesses identified him.

The problem: Research advanced by UC San Diego eyewitness and memory expert Dr. John Wixted has found that repeated showing of a suspect’s image to eyewitnesses causes their memories to be irreversibly contaminated. NCIP presented Wixted’s research, which also showed that the witnesses’ failure to initially identify Solorio itself actually pointed to his innocence.

And in October 2023, the district attorney agreed. “New documentable scientific consensus emerged in 2020 that a witness’s memory for a suspect should be tested only once, as even the test itself contaminates the witness’s memory,” the D.A. wrote in the office’s concession letter. The initial eyewitness tests showing that four witnesses did not identify him, “is powerful evidence of Mr. Solorio’s innocence,” the D.A. wrote.

False Testimony

NCIP found that Solorio’s case also was tainted by false testimony by a police investigator.

At trial, the investigator testified that Miguel’s alibi witness— his then-girlfriend Silvia—had not provided the investigator with critical information regarding the driver and vehicle used in the crime. In fact, a transcript of her police interview showed that she had. Neither the defense attorney nor the prosecutor— who knew or should have known the testimony was false—corrected the false testimony during trial, undermining Silvia’s credibility as his alibi witness.

Santa Clara Law student Caitlin Edwards and Santa Clara Law alumna Selamawit Solomon J.D. ’23 worked on  the case the entire 2022-2023 academic year. They summarized trial transcripts, attended strategy meetings, briefed legal issues, and helped draft Miguel’s habeas corpus petition.

the case the entire 2022-2023 academic year. They summarized trial transcripts, attended strategy meetings, briefed legal issues, and helped draft Miguel’s habeas corpus petition.

The experience has been profound. Edwards noted that Solorio went to prison the same year she was born. “It was a literal lifetime that he was locked up,” she said. “To be able to be a part of this, and to turn the wheels of justice no matter how slowly… was the best experience of my life and in law school.”

Laws Need to Catch Up with Science

Solorio’s is the third case in which L.A.-based clients represented by NCIP have been exonerated based on flawed eyewitness practices.

All three cases involved Latinx men, convicted at a young age and sentenced to life in prison. In each, eyewitnesses did not initially make positive identifications, but were allowed to later make positive identifications in front of the jury —at which point their memories had already been contaminated. The clients each ended up spending more than 20 years wrongfully incarcerated.

“The law needs to be changed to reflect the new consensus: a witness’s memory should be tested only once,” said Pace. “Lives are at stake.”