Camilla Amato

On September 23, 2018, the Santa Clara International Human Rights Clinic submitted an amicus curiae brief (in Spanish) before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (“Court”), addressing the issue of human rights violations and killings of environmental defenders in Honduras. In its judgment of September 26th, 2018 in the case of Carlos Escaleras Mejía v. Honduras, the Court adopted most of the Clinic’s arguments and stressed “the importance of the work of human rights defenders, which is fundamental to the strengthening of democracy and rule of law and which justifies a duty of the States to guarantee them special protection.”

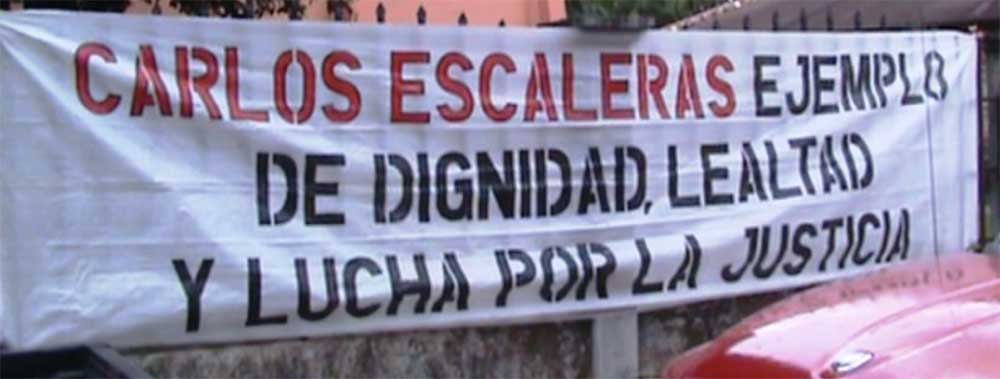

At the beginning of the semester, the Clinic decided to submit a brief to support the work of the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) in this case. Mr. Escaleras was one of the most recognized environmental leaders and defenders in Honduras, who denounced and opposed the activities of companies that harmed the environment and, more specifically, the Aguán Valley’s ecosystem with their dumping of toxic substances into rivers. As a result, Mr. Escaleras was pressured, threatened, and ultimately killed in 1997 at the behest of powerful landowners and business people in Honduras.

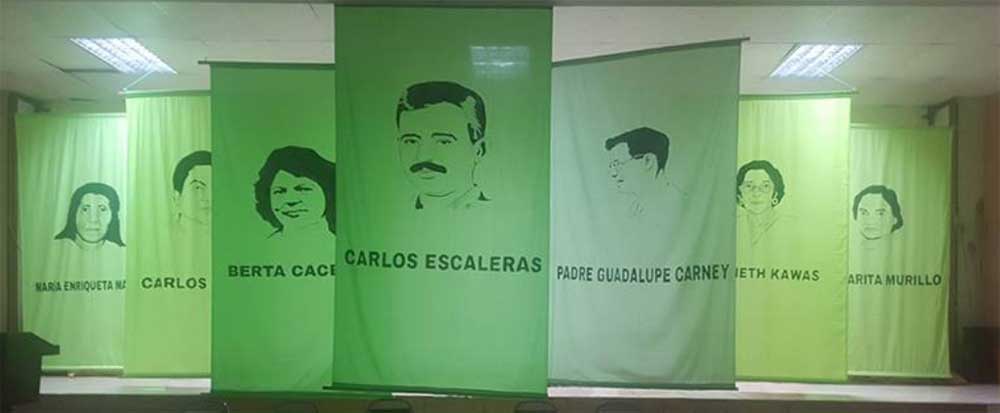

Honduran environmental activists who were killed for their activism.

In its petition before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, CEJIL, on behalf of Mr. Escaleras, alleged that Honduras violated the American Convention on Human Rights when it did not undertake an exhaustive and effective investigation to punish those responsible for Mr. Escaleras murder, and, more generally, did not adopt effective measures to prevent violence against environmental human rights activists. The case was settled just before it was scheduled for a hearing before the Inter-American Court; Honduras had agreed to make a joint request to the Court, together with CEJIL, to develop jurisprudence regarding a new human right, namely the autonomous right to defend human rights.

For us students at the Clinic, this meant that we only had two days to write an entire amicus curiae brief; any later, we would have risked having our brief rejected by the Court. With the tireless help and determination of Professor Rivera, we combined the research we had done so far and submitted the brief before the deadline.

With support from CEJIL, we prepared an amicus curiae brief that aimed to help the Court recognize and specify in more details the following: first, the scope of the autonomous right to defend human rights; and second, the corresponding obligations that States and businesses have in light on the American Convention on Human Rights.

Specifically, we recommended that the Court included in this new autonomous right to defend human rights, at a minimum, the enjoyment of the right to life, personal integrity, freedom of expression, freedom of association and access to justice (and should also recognize political rights, personal freedom, right to peaceful assembly, and the right to movement). Likewise, we expressed our view that the Court should recognize and specify in more details the obligations that all States and businesses have to respect the right to defend human rights and to provide remedies for the negative impacts that their activities cause in the enjoyment of those rights.

The right to defend human rights has now been widely recognized by the international community (namely, by the European, African and Inter-American systems) as an autonomous right that requires adequate protection. Nonetheless, despite near universal consensus, the Inter-American Court still needs to specify the scope of the right to defend human rights, in order to develop a more precise, detailed and binding jurisprudence. We also advised the Court to recognize the applicability of this autonomous right to all environmental defenders, which comprise a particularly vulnerable group, especially in Honduras.

Lastly, we advanced the argument that the right to defend human rights affects not only the defenders or activists who become victims, but our society as a whole. In the words of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “the attacks on the lives of human rights defenders have a multiplying effect that goes beyond the affectation to the person because, when the aggression is committed in reprisal to their activity, it produces an effect intimidating that extends to those who defend similar causes.”

In sum, we urged the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to develop its jurisprudence on the autonomous right to defend human rights so that defenders and activists will be entitled to extra protection and, hopefully, States like Honduras, will take their duties to respect, protect, and guarantee human rights more seriously.

Unfortunately, in its judgment the Court did not explicitly recognize that the right to defend human rights is an autonomous right under the American Convention. Nevertheless, the Court emphasized that “human rights defenders should benefit from special protection by the States, since the defense of human rights can only be freely exercised when these persons are not victims of threats or any other physical, psychological or moral aggression or any other kind of attack.”